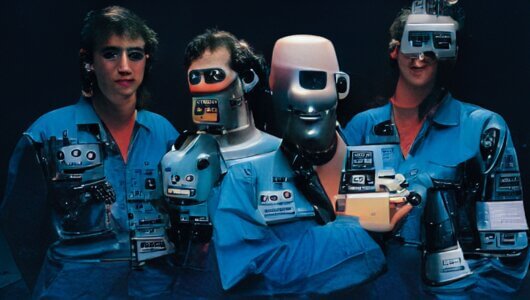

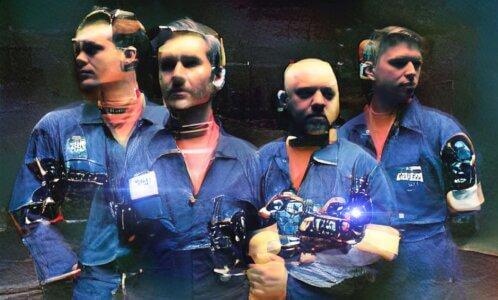

Jonathan Higgs from Everything Everything

Only in 2016 could listeners get the opportunity to dance or thrash their bodies around to a song about young people joining ISIS. Or mass shootings. Or civil unrest. That’s what you get with Manchester alt-pop outfit Everything Everything’s latest release Get To Heaven.

“I think when the music matches the theme its kind of one-dimensional,” frontman Jonathan Higgs said. “I want it to go deeper and people can dance to it if they want and they can think about it if they want.”

Higgs thinks a lot. About the state of the world, about humankind, about the way we’ve evolved—or perhaps devolved. How the population would handle a potential apocalyptic situation.

“If there was a crisis and we lost all our power and our cities—what are we? Can we even survive any more?” he questioned. These existential musings come through on Get To Heaven.

Out last June, Everything Everything waste no time delving into discomfort and tenseness on their third studio release, introducing imagery of a world on the brink of societal collapse, narrators struggling with inner turmoil, longing for a time not far removed. But there’s levity in the juxtaposition of the weight of words, penned by Higgs, and the spirited and twitchy musical arrangements of bassist Jeremy Pritchard, guitarist Alex Robertshaw and drummer Michael Spearman. Get To Heaven welcomes the musical intricacies of math and prog rock, vocals fit for a stadium and lyricism for the socially conscious.

Inspired by Higgs’ consumption of world news in 2014, Get To Heaven builds on Everything Everything’s repertoire—including 2010’s Man Alive and 2013’s Arc—of current event-focused sonic narratives, balanced by convention-pushing rock, packaged as an unlikely pop-structured work.

Higgs took a break from a bit of production work to chat with us on the human condition and how music is the perfect platform to discuss it without being preachy.

Northern Transmissions: How has the last year been with the album’s release and touring?

Jonathan Higgs: It feels like the record really connected in the way we wanted it to. It works really well live. People seem to know all the songs, people seem to want to hear the new record—and that’s not always the case when you put one out, people want to hear the old ones quite often. But in this case, everyone was there for the new record and that feels really, really good. It feels like you’re moving in the right direction and people understand what you’re trying to do. Especially when it’s something a little bit different, there’s always that worry when it comes out like “Are people going to accept this?”

NT: The album does really connect with people. It’s relatable for listeners regardless of where you are in the world.

JH: Yeah, I hope so. Sadly, I guess you could say a lot of it’s become all the more precedent, really. It feels like it’s more relevant now. We went to Paris about a week after the attack on the Bataclan. That was pretty crazy how I’ve written songs in the past and a lot of it is kind of too real.

NT: It’s scary and sad that this is the state the world is in.

JH: Yeah, it is. I’ve written a lot of lyrics that were about a slightly more exaggerated reality and that seems like it mirrors reality now. So maybe I’ll write some nice, positive stuff next and that’ll come true.

NT: Maybe you should write a children’s album.

JH: Yeah, and everyone will turn into children.

NT: Going into it, were you looking to make a grand political or social statement with the record?

JH: No, I don’t think there was a statement you could take away from it or a message. I never come down hard on either side of anything and that was really intentional. I don’t think it’s much fun to hear someone preach about rights and wrongs and I don’t think I’m in a position to requite on it, really. A lot of what I wanted to say was “This stuff is real and it’s happening and I don’t understand it myself. Does anyone else feel it themselves?” That’s what it’s about, trying to connect with other people who also didn’t know what the hell was going on and didn’t know what to think about and how to react.

So much reaction in the media was to make everything black and white and say “Well, these are obviously evil people and we don’t want them here and we don’t understand them. We’re just going to bury our heads in the sand and hope it goes away and then we’ll bomb them.” And I just wanted to say, “What is really happening?” and try to understand it on a more human level and try and put myself in the heads of some of these people. And as uncomfortable as it may be, try to find out why rather than washing my hands of it or not talking about it. It’s kind of a weird thing to do in a pop band but I really felt strongly that I wanted to acknowledge it in some way.

NT: It must be hard because no matter how “evil” someone might be perceived, they’re still a human and they still have though processes.

JH: It’s so easy to say, “Oh, they’re evil,” and forget about it. But it doesn’t really stop it happening again or it doesn’t help you get closure for why things are happening. You need to understand things so you can solve them. All we’ve got is more and more reactionary as time goes on. It’s gotten quite bad in Europe in terms of immigration because every time there’s an event people don’t really understand it and they just lash out. Obviously, I’m not really going to put any part in changing that but I want there to be some deeper thought about it and think well, what is the reality of the world we’re in and not this false one.

NT: Have you gained any clarity from that?

JH: No, I’ve certainly found other people that feel similarly and that’s the comfort in some way. I’ve found comfort in people who can recognize the stuff I’m talking about. What can you do as an artist? You can talk about what’s happening. You can’t tell people what to think—and I don’t like it when people do that. I just want there to be a connection between people and that feels like it’s happened with the record. Lots of people have said to me, “I really understand what you’re doing here.” It’s good to have an outlet for these feelings and it’s good to have a hold on the fact that no one’s got a hold on it rather than privately thinking to yourself “I don’t know what the fuck is going on and I don’t get this.” At least we’re all talking about it.

NT: It’s like a collective “What the fuck is going on?” moment.

JH: And I think that’s more important than people realize. People like to act like they do know what’s going on or that it’s in the hands of someone else and it doesn’t matter to them. It does matter when it gets closer and closer to us. No one really knows how to solve it. The least we can do is talk about it.

NT: And music is such a great medium to get people to talk about things.

JH: Exactly. I want it to be music that gives you release and gives you a place you can go. There’s no point in being unpleasant with it. I want music to be uplifting and hopeful even if the subject matter is dark and less hopeful.

NT: In the lyrics, there are a few allusions to getting older. Do you have a fear of death and mortality?

JH: I think less than I used to. I’m more concerned about aging rather than death. Death kind of deals with itself, you’re not really there for it. I’m getting older, I’m stepping more into the role of wise, older person talking to younger people in my songs rather than I used to and it’s kind of a weird transition. Obviously it’s a pretty immature sentiment to sing, ”I don’t want to get older,” but it came out my mouth—and it’s true.

NT: In examining your body of work, your albums are sort of anthropological studies in how humankind is behaving and things they’re experiencing at the time you’re writing.

JH: I definitely think of that kind of stuff a lot of the time—try and remove myself from my own views and look at the bigger picture. We’ve got front row seats in the greatest show in the galaxy. It’s so easy to get caught up in your own private world. There’s so much world out there. It’s so much of a bigger scale. Where are we going? Are we actually doing well? Are we successful? I find myself thinking about human life before civilization and the moment we stopped being animals because it’s absolutely fascinating. I can’t stop thinking about the differences between us and animals and all we’ve done with our thumbs and our brains and where it’s all headed.

Interview by Allie Volpe

Latest Reviews

Tracks

Advertisement

Looking for something new to listen to?

Sign up to our all-new newsletter for top-notch reviews, news, videos and playlists.